What is CTE?

CTE, Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is a brain disease that is degenerative and progressive.

CTE occurs as a result of repetitive head impacts (RHI). CTE has been found in people with or without a history of concussions. Concussions may add to the likelihood of getting CTE, but the biggest factor seems to be the length of time exposed to repetitive hitting, and the force of that hitting. CTE was originally only thought to exist with boxers but it was later discovered in victims of physical abuse, head banging and poorly controlled epilepsy. Now it is being associated with athletes playing contact sports including American football, ice hockey, soccer, wrestling, extreme sports, as well as veterans and military personnel with a history of being exposed to repetitive blows from training or blasting. One of the largest concerns is the growing discovery of CTE in high school and college athletes and tragically athletes who only played sports at the youth level.

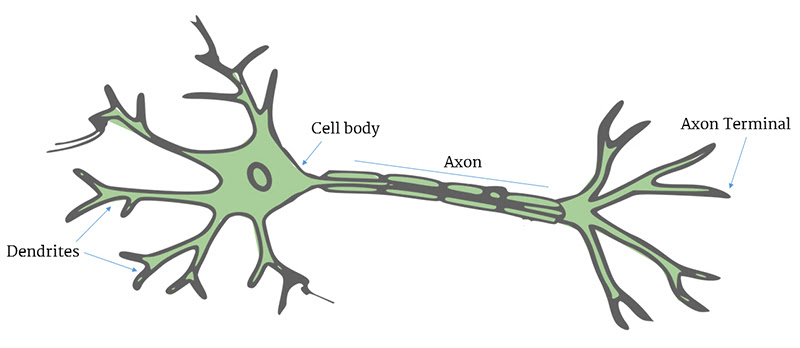

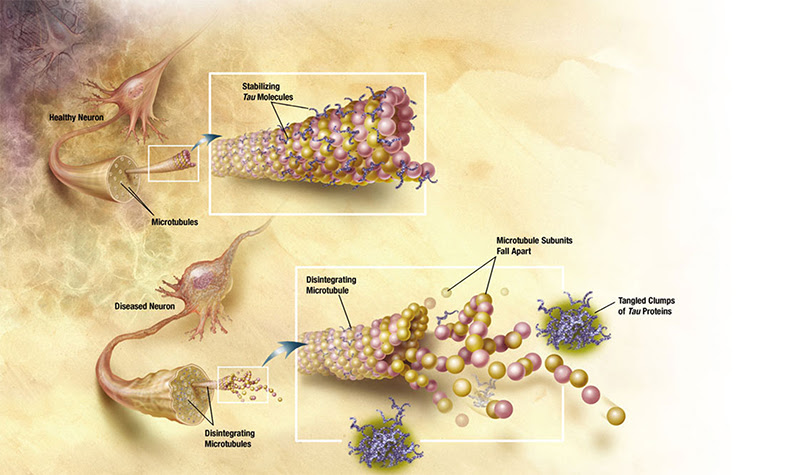

The brain of a person with CTE gradually deteriorates and tau proteins begin to become defective and interfere with neuron functioning. At the current time CTE can only be verified through a specific autopsy. But there is a growing consensus among researchers that see the possibility of a clinical diagnosis of CTE, or TES (Traumatic encephalopathy syndrome). The clinical presentation of CTE usually begins with a lack of behavioral control: explosivity, impulsivity, rage behaviors, paranoia, violence, and loss of control. In most cases mood behaviors such as depression and anxiety occur. Memory issues, executive functioning deficits, and attention problems have also been noted. Addictive behaviors and suicidal thinking are also associated with CTE. Since often times the onset of CTE symptoms occurs many years after the repetitive head impacts (RHI), it is imperative for doctors, family members, morticians, policing entities, and rehab facilities to look for the possibility of CTE through examination of the history of each individual.

Please also see:

https://stopcte.org/what-is-cte/symptoms-of-cte/

See the CDC Fact sheet on CTE at this link: